At first blush, this would appear to be a no-brainer. We live, experts remind us, in a celebrity driven culture where consumers are dying for a glimpse of their favorite celebs. Really? Then why are ratings for the Oscars–a sort of All-Star Game for celebrities–at historic lows?

There are a plethora of questions that need to be asked whenever contemplating using a celebrity endorser.

How popular is she/he? Celebrities are given a “Q” rating which measures their potential clout as advertisers. Of course, the more popular “Q”

raters are already endorsing, which means their endorsement would have diluted impact for the next product. People who watch a lot of television might sniff, “Big deal. She endorses everything.”

To some extent, the celebrity should have a relationship with–if not represent a match–for the product being endorsed. Their was a point in time when having Tiger Woods rep cars wasn’t funny. Does it make any difference that actor William Devane buys gold? Is there anything about Devane that says “financials?” Would anyone in a tie do just as well?

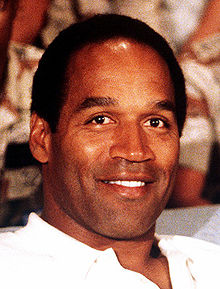

What happens if the celeb goes bad? Even after the campaign is over? For example, O.J. Simpson was retired as a spokesman long before his trial for murder, but anyone who remembers the airport granny yelling “Go, OJ, Go!” could probably tell you it was ad for Hertz.

Why bother having a celebrity as the face of the product–celebrities have to be coddled and pampered–when any old duck (AFLAC) or lizard (GEICO)

will do. The duck isn’t going to cause the advertiser any trouble, though it’s worth noting that the duck’s voice Gilbert Gottfried did get dumped because of intemperate remarks outside of the AFLAC arena. The lizard has managed to stick around for years on the basis of a thin joke, that Geico sounds like “gekko.” But by any measure this is one of the most famous and long-running campaigns in history. Consumers may find the cartoon animal endorser as appealing as a real person.

With consumers more media sophisticated, everyone knows celebrities endorse for money. And yet, the whole point of the celebrity endorsement is the sense of genuineness or honesty the celebrity brings to the endorsement. There’s an inherent conflict here. If the endorser comes off looking smarmy, i.e., the audience gets the idea that the only reason he’s doing the endorsement is because he’s getting paid, or worse yet, is “desperate,” it defeats the whole purpose of the celebrity endorsement.

In a multi-cultural kind of society, what advertisers want you to know is that they’re OK with different kinds of demographics. That’s why today you’ll see groups of people representing different backgrounds in commercials. Using a celebrity endorser runs the risk of a consumer saying, “They don’t represent people like me.”

Celebrity endorsements aren’t going away, but marketers should consider that one ad campaign’s celebrity star is another campaign’s AFLAC duck.